High need babies are known for their sensitivity and intensity.

High needs is a continuum, of course, but most high need babies tend to fall on the high end of the scale when it comes to these two traits.

Because of this, many parents begin to wonder and worry that there may be something more going on.

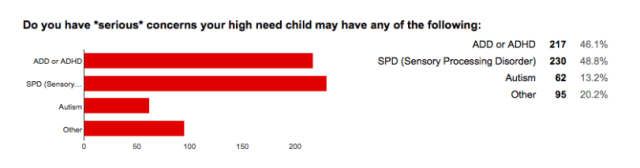

In fact, in a survey I did of over 1,400 parents of high need babies last year, 36% of parents said they had serious concerns about this. Of this group, almost half were seriously concerned about Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD).

What is Sensory Processing Disorder?

SPD is a condition in which the brain has trouble receiving the data it needs to properly deal with sensory input. Considering that we need to react and respond to countless sensory inputs throughout the day (cool air blowing on your face, a scratchy tag tickling your neck, the sour taste of a not-quite-ripe piece of fruit), it’s not surprising that people with SPD can become easily frustrated and overwhelmed.

In her book, Sensory Integration and the Child, occupational therapist and neuroscientist A. Jean Ayres compares SPD to a sensory traffic jam: “When sensations flow in a well-organized or integrated manner, the brain can use those sensations to form perceptions, behaviors, and learning. When the flow of sensations is disorganized, life can be like a rush hour traffic jam.”

If you can imagine what it must like for a small child to cope with all the sensory input they receive during the day, it’s not hard to understand why they may often fuss or cry, or have frequent tantrums.

What are the symptoms of SPD in infants and toddlers?

I reached out to Nancy Peske, co-author of the book Raising a Sensory Smart Child: The Definitive Handbook for Helping Your Child With Sensory Processing Issues, to ask her about the signs and symptoms of SPD.

According to Nancy, one of the most common red flags of Sensory Processing Disorder in young children is a developmental delay in receptive and expressive language, and fine and gross motor skills.

Because parents are often comparing their child’s development to what they read about in books or hear from their doctor, this is often the first sign that something else may be going on.

Other signs of SPD in young children include:

- Difficulty falling and remaining asleep without external soothing

- Trouble latching on to breastfeed

- Tantrums and crying that are more intense and last longer than they do for most babies and toddlers

- Especially clingy and difficulty self-soothing or being soothed by someone other than the primary caregiver

- Very picky about how he or she is held

- Very high or very low pain threshold

- Constantly on the move

- Clumsy, uncoordinated, drops items often

- Trouble shifting focus from one activity to the next or one toy to the next

- Doesn’t like rocking at all OR wants to rock all the time

- Very distressed or even nauseated by swinging OR won’t come out of the baby swing without wailing because she loves swinging so much

- Very sensitive to certain sounds, too much light or a certain quality of light, temperature, sights including certain colors or a busy visual field, a lot of sounds at once such as people singing in unison, being touched unexpectedly, pressure against the skin (in other words, a light touch may be very distressing compared to a heavy touch, temperature, clothing fabrics, and so on). Think extreme responses to everyday sensations.

- Constantly sensory seeking—touching, tasting, etc.—more so than most babies and toddlers. For example, the baby might enjoy sucking on a lemon!

- Upset by having to transition from one sensory environment to another, such as from a warm room to a cool one

- Eating difficulties, such as transitioning to solid foods, keeping the food together to chew it and swallow it effectively

- Excessive drooling

- Slow to toilet train

What is ‘high needs’?

While some people assume that all babies are ‘high needs’, research tells us that this isn’t actually the case. While all babies require lots of love, care and attention, some babies require nearly constant soothing, holding and distraction to keep from fussing or crying.

As I wrote about in my post, Is There Really Such a Thing as a High Need Baby, researchers discovered in the 1960’s that temperament could be identified in infants very early on.

According to this groundbreaking study (which you can read in its entirety here), around 10% of all babies were identified as being “difficult”: meaning they demonstrated high levels of intensity, were more sensitive to stimuli, were irregular in terms of eating and sleeping habits and were generally more negative in mood (i.e., grumpy).

In the summary of their findings, the study’s authors wrote:

“These children are irregular in bodily functions, are usually intense in their reactions, tend to withdraw in the face of new stimuli, are slow to adapt to changes in the environment and are generally negative in mood. As infants they are often irregular in feeding and sleeping, are slow to accept new foods, take a long time to adjust to new routines or activities and tend to cry a great deal. Their crying and their laughter are characteristically loud. Frustration usually sends them into a violent tantrum. These children are, of course, a trial to their parents and require a high degree of consistency and tolerance in their upbringing.”

The 12 traits of the high need baby

Popular attachment parenting guru Dr. Sears later coined the term “high need baby”…a somewhat nicer way to describe these difficult babies. He also identified the 12 features of the high need baby, which are in line with the traits assigned to infants in the research study mentioned above.

According to Dr. Sears, the 12 traits of the high need baby include:

- Intense

- Hyperactive

- Draining

- Feeds frequently

- Demanding

- Awakens frequently

- Unsatisfied

- Unpredictable

- Super-sensitive

- Can’t put baby down

- Not a self-soother

- Separation sensitive

Keep in mind that “high needs” is not a physical condition, but is simply a way of describing a particular set of behaviours. While babies can exhibit high need behaviours because of physical conditions like reflux or food allergies, oftentimes it’s simply an early sign of a strong temperament.

While temperament generally doesn’t change over a person’s lifetime, high need babies do tend to become easier and more adaptable as they get older and reach new milestones.

As they get older, we tend to refer to these kids as “spirited”. For more on the traits of spirited babies, kids and adults, see our post Characteristics Of The Spirited Child.

As you can see, many of the signs and symptoms of SPD are similar to the traits we see in high need or “difficult” babies. But does this mean all high need babies have SPD? Or that all babies who have SPD are high needs? The lines can get blurry, for sure.

Nancy very generously answered my questions regarding SPD, including how to differentiate between SPD and high needs. The rest of this post is taken directly from my interview with Nancy.

How do you know if it’s SPD or high needs temperament?

[When kids] have sensory issues, they also often have difficulty learning through their senses as we are meant to do, so they very commonly have developmental delays. Their brains just aren’t putting it all together correctly to make sense of what’s going on in their bodies and environments.

Many kids are picky about textures of clothing or food, but a child with Sensory Processing Disorder may become extremely distressed about having to touch or eat something with what is, to them, a repulsive texture.

Punishment and reward don’t work. You see a lot of anxiety about being pushed to do something that is distressing to their sensory system, or that they fear will be distressing.

They might love when Daddy or Mommy sings a lullaby, but if both sing at the same time, it’s too challenging to process the complex sound and they become distressed.

The child with SPD typically has difficulty with transitions but may be just fine with many transitions as long as they don’t involved something sensory.

They’re fine if the ice cream store turns out to be closed, but if you suddenly say, “Hey, Daddy just called. He’s coming home and we’re going to the ice cream store, so put your shoes on”, they scream because you just told them “put your shoes on”—a distressing sensation. It’s not about getting that yummy ice cream, or the transition, in this case. It’s about the sensations.

Inconsistency is the hallmark of sensory issues.

The child who [usually] tantrums, or who runs in circles, laughing and is clearly overstimulated at bath time, might suddenly [one night] be super calm at bath time.

Why? [It may be because] for the first time you just happened to close the door when the tub was filling. So, while you were undressing him, he didn’t hear the intense sound of the water from the faucet hitting the porcelain tub, and he didn’t hear that sound bouncing against the tile on the bathroom wall and floors.

It was muffled, and his response to bath time is totally different as a result.

Do most high need babies struggle with sensory issues? And if this is the case, would you say they have SPD?

(Note from Nancy: I don’t work with babies, or high needs ones—I work with parents and it is unusual for parents to talk about babies under age 2. They typically are hearing about sensory issues as part of birth-to-three, and their questions aren’t about newborns, or babies just sitting up—they tend to be about behaviors you see at a year or more.)

Sensory processing issues are more common in premature babies, babies who have been sick or had medical procedures when they were very, very young, and babies adopted from foreign orphanages. There may be a genetic component, and poor prenatal care and toxins encountered by the baby when developing may influence the child, too.

We don’t know the exact cause of sensory issues. We just know what the correlations are.

Sensory processing differences are on a spectrum. Sensory Processing Disorder is the term for when sensory issues are interfering with a child’s activities of daily living.

For a baby, [those daily activities] include sleeping, eating, getting potty trained, socializing with people (“Smile for Daddy!”), communicating (“Which toy do you want? Show me!”) and learning.

Are there any normal infant or toddler behaviors that commonly get mistaken for SPD?

Again, because sensory processing differences are on a spectrum, you have to think of them as a problem if they are interfering with activities of daily living, but with very young babies, it can be hard to see that unless you are seeing delays.

But let’s say your toddler won’t sit down to eat. I mean, he really won’t sit down, or if you coax and bribe him to, he falls off the chair.

Then, you offer him an inflatable bumpy cushion and the problem is solved because now he can feel that chair underneath his bottom. Looking at the behavior through a sensory lens can help you understand his behaviors and work more effectively with him.

If you think in terms of sights, sounds, smells, taste, touch, body awareness (proprioceptive sense), and his sense of movement (vestibular sense), it is easier to see sensory issues.

How early can and should SPD be diagnosed?

An OT (occupational therapist) uses SPD as a functional diagnosis. It’s something that is affecting the child, so when she is looking at developmental delays such as difficulties with eating, sitting up, and so on, she will be looking at sensory issues.

Typically, a parent alerts her doctor (or her doctor alerts her) to signs of developmental delays, and gets the baby evaluated for them. An OT would be evaluating the child as part of the evaluation process.

So, if you were calling your state’s birth-to-three program/early intervention program, you would want to mention any signs of sensory issues and ask for an occupational therapist to evaluate the baby for sensory issues that might be interfering with her development.

What steps should parents take if they see behaviours that they think are SPD?

First, you would want to do a preliminary sensory profile just to get a sense of your child’s unique sensory portrait. You can find this in Raising a Sensory Smart Child and on my website, www.SensorySmartParent.com.

Then, if you are concerned because your child is not meeting his developmental milestones (which again, you can find in the book), consider an evaluation for developmental delays as well as for sensory issues.

You will want to work with an occupational therapist who is trained to evaluate for, and treat, sensory issues in babies and toddlers.

What are some good resources for learning more about SPD?

My book, Raising a Sensory Smart Child: The Definitive Handbook for Helping Your Child with Sensory Processing Issues is not only chock full of information and strategies, it is also loaded with specific resources.

For example, you might want your toddler or preschooler to do a listening therapy that would address, specifically, auditory processing issues. You can learn about auditory processing disorders (there is more than one type) and find information about these programs in the book.

Also, the Facebook page for Raising a Sensory Smart Child is a place to find new information and join in the community discussion. And if you sign up for my newsletter at www.SensorySmartParent.com, I will alert you to seminars, lectures, and webinars about sensory issues that you may be interested in.